April 15, 1912

Another busy day, so let's get right to it, shall we? Apologies in advance for the length.

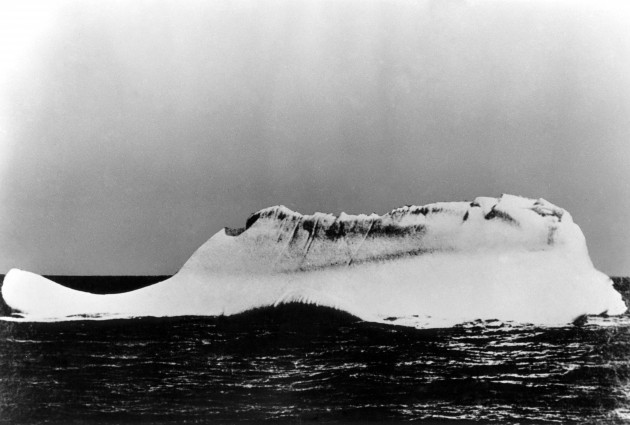

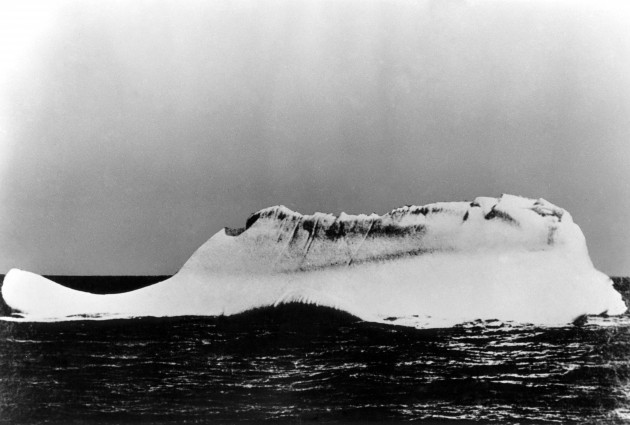

Twenty minutes after striking an iceberg, Captain Smith had been made aware of the ship's fate, and it wasn't a good one: Thomas Andrews estimated she had only an hour and a half or so left to live. Smith headed for the wireless room and told Phillips to start sending out their position with CQD (the international distress signal, which had recently been replaced by SOS, but most operators hadn't adopted the new code yet). Around 12:05, the first distress call was sent. At this point, the severity of the situation wasn't as clear, and Phillips and Bride made jokes as they sent their messages. (Photo is one of the icebergs seen the next morning that is a possible candidate for the one Titanic struck.)

Twenty minutes after striking an iceberg, Captain Smith had been made aware of the ship's fate, and it wasn't a good one: Thomas Andrews estimated she had only an hour and a half or so left to live. Smith headed for the wireless room and told Phillips to start sending out their position with CQD (the international distress signal, which had recently been replaced by SOS, but most operators hadn't adopted the new code yet). Around 12:05, the first distress call was sent. At this point, the severity of the situation wasn't as clear, and Phillips and Bride made jokes as they sent their messages. (Photo is one of the icebergs seen the next morning that is a possible candidate for the one Titanic struck.)

Smith's next order was to begin readying the lifeboats. Below decks, passengers were milling about more, trying to figure out why the ship had stopped. Most of the crew still hadn't heard any news from above, so many of them reassured their charges that everything would be fine. Some believed them and returned to their cabins, while others were more cautious and went out on deck to see for themselves. Many returned to their rooms to get dressed first, or at least covered their pajamas with coats and swapped their slippers for shoes.

About twenty minutes later, the captain finally gave the order to start mustering passengers up on deck in their lifebelts to load the boats. Women and children first was the rule of the sea at the time, and as the night progressed, some crew would enforce this more strictly than others.

About this time, 58 miles away, the Carpathia's lone wireless operator, Harold Cottam, was getting ready to shut down for the night. He would have already done so, but was waiting for confirmation on a message he had sent out. While he waited, he heard some messages being transmitted for Titanic and started to jot them down. He then switched to Titanic's frequency to pass them along. The following is the conversation that transpired.

Carpathia: I say, old man, do you know there is a batch of messages coming through for you from MCC? [MCC = Cape Cod]

Titanic, breaking into Carpathia's message: Come at once. We have struck a berg. It's a CQD, OM. Position 41° 46' N 50° 14' W

Carpathia: Shall I tell my captain?

Titanic: Yes, come quick.

Cottom ran to the bridge to inform the watch officer, H.V. Dean. Together, they went below to the cabin of their captain, Arthur Rostrom, who had just turned in for the night. Despite his initial irritation at the disturbance, he quickly realized the gravity of the situation and began dressing. He checked Titanic's coordinates in the chart room and ordered the ship to change course and had more stokers brought on duty so they could steam for the foundering ship at top speed (which for them was usually 14.5 knots, although they ended up reaching 17.5 knots that night). He ordered all unnecessary equipment shut down (including the ship's heaters) so that all the steam could be directed to the engines, and put four extra lookouts on duty to make sure they didn't barrel into any ice themselves along the way. With this added speed, the original estimated arrival time of 4:45am was beaten by about an hour. Unfortunately, they weren't fast enough. By the time they arrived at Titanic's location, there was nothing there but flat, calm sea.

Even closer to the Titanic, the Californian was stopped for the night, surrounded by ice. She had already tried to make contact with Titanic, but was rebuffed by a frazzled Phillips and told to keep out. By the time Titanic started sending out CQD calls, their wireless officer, Cyril Evans, had gone to bed. But other officers were up and about, and around the time Captain Rostrom was turning the Carpathia towards rescue, a fireman on Californian was having trouble sleeping. Earlier, he had spotted "a very large steamer, about ten miles away" as he came off of his 8-12 shift, and when he went back on deck to get some air, he noticed a white rocket from that direction. Thinking it was a shooting star, he waited, then saw another. In his words: "It was not my duty to notify the bridge or the lookouts. I turned in immediately after."

Other officers on the ship also noticed Titanic off in the distance, but none were ever too concerned. Many believed the ship they saw to be a smaller fishing boat, and while some did see the rockets she fired, they didn't believe them to be distress rockets. They tried to signal her with their Morse lamp a few times, but never saw any response. The Californian's captain, Stanley Lord, kept in contact with his watch officer, Herbert Stone, for a few hours, getting updates about the ship they'd been monitoring.

The Californian wasn't the only ship nearby who didn't come to the Titanic's aid. A smaller ship, the Samson, was close enough to see the ship as rockets were fired, but they were illegally hunting seals, and misinterpreted the rocket for a government signal. Afraid they were caught, they turned off their lights and sailed away. Many years later, the ship's captain would confess on his deathbed what he had done, saying if they had stayed to help, they might have been able to save 500 to 1000 people. Many survivors would tell of a "mystery ship" they had noticed only a few miles away and tried to signal as they were sinking, only to watch it disappear. Many believe this to be the Samson.

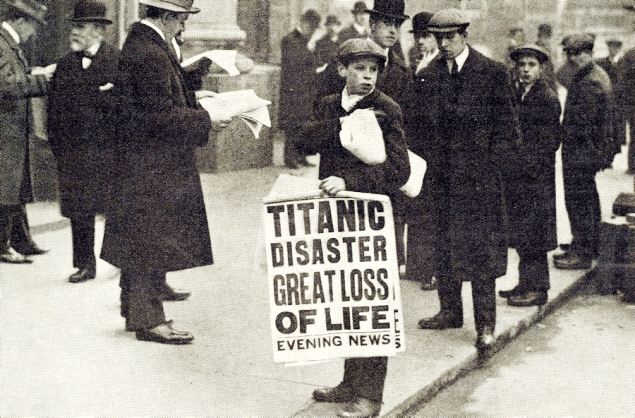

Back on the Titanic, news was finally spreading about the danger. Stewards were knocking on doors, waking passengers and ordering them on deck with their lifebelts. Still, most did not believe anything serious was happening. Their faith in the ship was unwavering. The officers, however, knew better. In his book, Titanic and Other Ships, Second Officer Lightoller, recounted the following:

Having got the boats swung out, I made for the Captain and happened to meet him near by on the boat deck. Drawing him into a corner, and cupping both my hands over my mouth and his ear, I yelled at the top of my voice, "Hadn't we better get the women and children into the boats, sir?" He heard me, and nodded reply. One of my reasons for suggesting getting the boats afloat was, that I could see a steamer's steaming lights a couple of miles away on our port bow. If I could get the women and children into the boats, they would be perfectly safe in that smooth sea until the other ship picked them up; if the necessity arose. My idea was that I would lower the boats with a few people in each, and when safely in the water fill them up from the gangway doors on the lower decks, and transfer them to the other ship.

I've always found this interesting, because not only does it explain (a little) why so many boats weren't filled completely, but also shines a light on what the captain's state of mind may have been. If you believe Lightoller's account, he appears almost stunned into inaction, needing a nudge from the other officers to make the necessary decisions to evacuate the ship.

Steam was now escaping from the funnels, the noise of which was nearly deafening. Passengers huddled indoors where it was warmer and quieter, still believing that the danger wasn't serious. The steam lasted for about 10 minutes, then silence returned. At this point, the ship's orchestra set up in the first class entrance and played to entertain the passengers that waited there. According to Lawrence Beesley, they moved outside to play on deck around 12:40, and kept it up until well past 2am.

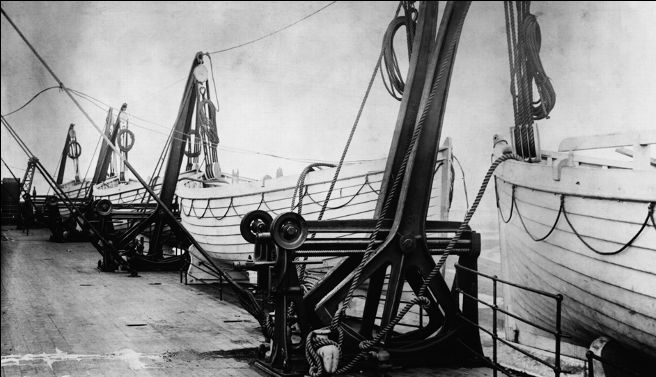

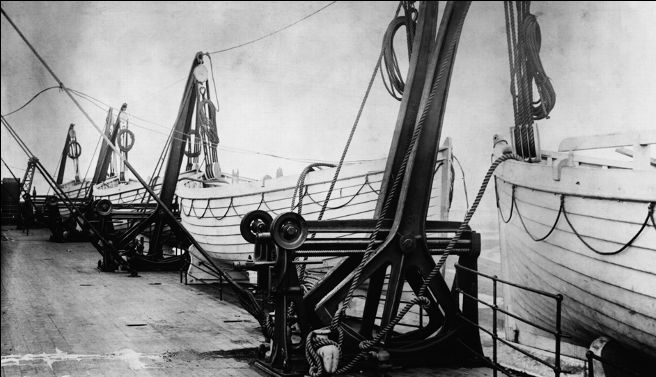

Around 12:45, quartermaster Rowe began firing distress rockets. He would fire them at five-minute intervals for about 40 minutes. Meanwhile, the lifeboats were finally ready to be lowered. On the starboard side, First Officer Murdoch, Third Officer Pitman and Fifth Officer Lowe were in charge. Over on the port side, Lightoller was overseeing the boats with the help of Chief Officer Wilde and Captain Smith. Lightoller started by lowering lifeboat #4 down to A deck, where a group of wealthy first class passengers (including the Astors) were waiting. His intention was to load the boat from there, keeping them slightly warmer (the A deck promenade was enclosed) as they waited. But the screens could not be opened without a special tool, so he eventually had to give up and return to the boat deck, leaving #4 hanging there while he loaded the other boats.

Around 12:45, quartermaster Rowe began firing distress rockets. He would fire them at five-minute intervals for about 40 minutes. Meanwhile, the lifeboats were finally ready to be lowered. On the starboard side, First Officer Murdoch, Third Officer Pitman and Fifth Officer Lowe were in charge. Over on the port side, Lightoller was overseeing the boats with the help of Chief Officer Wilde and Captain Smith. Lightoller started by lowering lifeboat #4 down to A deck, where a group of wealthy first class passengers (including the Astors) were waiting. His intention was to load the boat from there, keeping them slightly warmer (the A deck promenade was enclosed) as they waited. But the screens could not be opened without a special tool, so he eventually had to give up and return to the boat deck, leaving #4 hanging there while he loaded the other boats.

At this time, over on the starboard side, lifeboat #7 would be the first to successfully launch. The bad news: it is woefully under-filled. A capacity of 65 people, it left Titanic with only 28 aboard (plus one Pomeranian, according to some accounts). One of those was actress and model Dorothy Gibson, who would later appear in the first movie ever filmed about the Titanic disaster, Saved From Titanic. The rest of the 28 were other first class passengers and three crew members put there to help navigate: two lookouts and a seaman. In the officers' defense, they tried to get more people on the boat, but they had all refused, still believing that there was no danger, and that they would be safer (and warmer) on the Titanic.

Also around this time, below decks, the bulkhead between boiler rooms 5 and 6 collapsed, filling boiler room 5 with water and drowning nearly every man inside. This is the wall where the fire in boiler room 6 was burning for so many weeks, and speculation is that the fire weakened it and caused this collapse.

(The exact order of the launching of lifeboats is different in every book I've read, as are the times, so I may not have this quite right.)

About 10 minutes later, the next two boats were lowered, #5 on the starboard side and #6 on the port side. Lifeboat #5, with a capacity of 65 people, was lowered with between 30 and 40 on board (exact numbers are also hard to pin down). J. Bruce Ismay stood by as it was being lowered, shouting "Lower away! Lower away!" and waving his arms frantically until he was told by Officer Lowe to get out of the way and let him work. As it was lowered, a man from first class jumped in, landing on one of the women and breaking two of her ribs. Over on the port side, lifeboat #6, also with a capacity of 65, was lowered with about 26 on board. (Some accounts show this lifeboat leaving later) Among those on board: Margaret "Molly" Brown, who was pitched in by a crewman as the boat was being lowered. Only two men were on board, Quartermaster Hitchens and lookout Frederick Fleet, so they called out for more aid. A passenger and yachtsman, Major Arthur Peuchen, volunteered and scaled down the ropes into the boat. Later on, tension would develop between Hitchens and the rest of the passengers. He resisted when the women offered to help row, and refused when they wanted to turn back and pick up more survivors.

Around 1:00am, Lightoller was supervising the loading of lifeboat #8. Ida Straus, wife of Isador Starus and owners of Macy's department store, was standing nearby, but when asked to get into the boat she refused, famously stating "I will not be separated from my husband. As we have lived, so will we die—together." They turned and went back into the ship, presumably to their cabin, and were never seen again. As with many of the other early boats, #8 was lowered with less than 30 people on board.

A few minutes later, lifeboat #1 was lowered from the starboard side, and would become one of the more talked-about boats later on. A smaller emergency boat, with a capacity for only 40, it was sent off with only 12 people on board: 5 first class passengers and 7 crew. Besides the absurdly low capacity, the fact that more crew than passengers were on board, and of that group, only two women, made for an even more dramatic story. While Lightoller was sticking to a "women and children only" credo over on the port side, his starboard counterpart, Murdoch, was being more lenient. He put some firemen on the boat with a couple of lookouts and a few first class men, instructing them to stay nearby to pick up other passengers later, when Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon showed up and asked if he and his wife (and her secretary) could board the boat. Murdoch happily allowed them. But once they were in the water, no one spoke up about returning, and they never did. During that time, one of the firemen commented that they had all lost their kits and would have to replace them. In an attempt to be helpful, Sir Cosmo offered to give them each five pounds to help them cover the cost, which he did later on. Unfortunately, when news of this kindness got out, he was accused of bribing them not to return to pick up more passengers, and was never able to live down the accusation.

At this point, Titanic was clearly in trouble. Her bow was pointed downward enough to be obvious she was sinking, and people were starting to panic. Lifeboat #9 was being loaded around 1:30am. Benjamin Guggenheim put his mistress on it, then stepped back with his valet and told a steward, "We've dressed in our best and are prepared to go down like gentlemen. There is grave doubt that the men will get off. I am willing to remain and play the man's game if there are not enough boats for more than the women and children. I won't die here like a beast. Tell my wife I played the game out straight and to the end. No women shall be left aboard this ship because Ben Guggenheim was a coward." Also on #9, second class ladies Kate Buss and Marion Wright, who were put on after an officer asked if any more women were nearby. Buss reportedly argued with the officer in charge of the boat after he refused to let their two male friend on with them.

According to third class steward, John Hart, the gates keeping third class passengers from the upper decks were opened around 1:15am, allowing them to come up and take their chances with the lifeboats. Many of them would not find their way above, due to the mass confusion and language barriers among the various nationalities in steerage.

Finally, those loading the boats wised up to the severity of the situation and began filling the boats more. Lifeboat #11 was lowered with over 50 people. There's a sad story connected with this one: a first class family, the Allisons, were preparing to leave the ship when their nurse took the baby, Trevor Allison, up on deck, determined to save him. She got on boat #11 and was saved, but there was a lot of confusion around her departure, and the rest of the Allison family was unaware she had gotten off the ship. They searched frantically for their son, but by the time they realized the nurse had taken him, the boats were all gone. None of the rest of the family survived, and their 2-years-old daughter, Helen, was the only child in first or second class to die.

The last two full-sized boats to leave the starboard side were #13 with about 60 on board, then #15. One of #13's occupants was Lawrence Beesley, who was instructed to jump on as it was being lowered once the officer in charge realized there were no more women around. This boat was nearly crushed as the next boat, #15 (loaded slightly over capacity), was lowered, due to escaping water pushing it underneath 15. Ropes were cut just in time and the boat was able to move away before anyone was injured.

Over on the port side, the difference in loading procedures was more apparent. While boats on the starboard side were leving filled with women, children and men, the port boats were still leaving half-full. Lightoller stuck firmly to women and children only, so when no more women were around, he would put a few crew members on the boat and send it on its way. #12 was lowered with only about 40 on board, then #14 with closer to 60. #14 was helmed by Fifth Officer Lowe, who would later corral it along with boat #4, #10 and #12, tie them together, then transfer passengers from one to the other to level them out. Once done with this, he and a few other officers took his boat, which was now emptied, back to the site of the sinking to look for survivors. They were the only ones who would do this, but they took too long to get out there and only managed to save 3 people, one of whom did not survive.

Next to load was #16, which included second class passenger Edwina Troutt and stewardess Violet Jessup. Jessup had already been through a rather major crash on Titanic's sister ship, Olympic, and would later be on her other sister ship, Brittanic, when it was sunk by a mine in the Aegean Sea. She was one of the only people who could say she survived all three disasters.

Another soon-to-be-notorious lifeboat, Collapsible C, was lowered from the starboard side with over 40 people on board, nearly all women. At one point while it was being loaded, a group of third class men supposedly tried to get on board, and one of the officers (some said Murdoch, others said Chief Purser McElroy) had to fire a couple of warning shots in the air to hold them back. These shots would be discussed at length over the next 100 years as debates raged over whether or not anyone was shot to death while loading the boats. As if that wasn't enough drama, as the boat was being lowered, J. Bruce Ismay, after spending the last hour assisting with the loading of the lifeboats, would climb in and save himself. Some called him a coward for this. Personally, I'm torn. On the one hand, yes, it looked bad for a man in his position to be saved in such a way, but on the other hand, the spot he took would have been empty had he not gotten in, so he didn't save himself at the expense of another.

Titanic was listing so far to port by this point that no more boats could be launched from the starboard side. The rest had to go from the port side, starting with emergency boat #2. As it was about to be loaded, it was discovered that a group of crew members had already gotten in. Angry, Lightoller brandished his pistol (he later claimed it was unloaded) at them and ordered them off. As with the rest of LIghtoller's boats, it was lowered about half full, with only women and a few male crew members. Among those crew was Fourth Officer Boxhall, who brought along a lantern and some green rockets. He would fire these off throughout the night, using them to signal the Carpathia when she arrived in the morning.

The last full-sized lifeboat to be loaded was #4, still hanging down by A deck where it was abandoned nearly an hour earlier. Someone had finally found the tool needed to open the screens, so the boat was loaded through the A deck windows with nearly all women, including Madeline Astor. Her husband, John Jacob Astor, asked if he could join her because she was pregnant, but Lightoller refused. Continuing with his determination to load only women and children, he nearly refused to let a 12-year-old boy on. When the boy's mother begged him, he grudgingly relented, saying "no more boys." One story claims that, upon hearing this, Mrs. Carter placed her hat on her own young son's head in order to be sure he'd be allowed on board. After Titanic sunk, the boat would take in swimmers from the water.

After this, it is said that John Jacob Astor went down to the kennels and released the dogs. It was now around 2am, and a group of first class passengers, uninterested in saving themselves, retired to the smoking room for a final game of cards, then left the room ten minutes later. A survivor also reported seeing Thomas Andrews in that room around that time, staring thoughtfully at a painting, his lifebelt laying forgotten on a table. I believe this is the account James Cameron used for his final shot of Andrews in the movie.

Around 2:05am, Captain Smith returned to the wireless room and told Phillips and Bride they were relieved from their duties, and to save themselves if they can. On his way out, it is said he told crew members it was now every man for himself, then reportedly disappeared into the bridge. Other survivors said they saw him swimming to one boat or another after the sinking, never trying to save himself, but there's no way to know which tale is true.

Also around 2:05, Collapsible D was filled not quite to capacity and lowered. Among its passengers were the two Navratil boys from second class, who had been traveling with their father under the name of Hoffman, as he had kidnapped them from their mother. They would be happily reunited with her later in New York, but their father went down with the ship. A few minutes later, the ship's orchestra began to play their final song. Debate rages still over its identity: some say it was "Nearer My God to Thee," while others insist it was "Autumn."

Only two collapsible boats were left: A and B, and both were still attached to the roof of the officers quarters. Men began trying to cut them down, but before they could, the ship took a slight dive, sending a wave over the bow and washing Collapsible B off the deck, upside down. Boat A was also washed off around that time, but it stayed upright. Not long after this, the wires holding the forward funnel snapped, sending it crashing into the water and killing whoever was swimming there (many believe one of those men was Astor, whose body was found crushed).

The angle of the sinking became greater, and everything inside the ship began to slide forward with a loud roar: furniture, dishes, even the gigantic boilers. Those still on the ship ran for the stern to cling to the rails, still desperate to stay on board. Down in the wireless room, Phillips sent his last message at 2:17am, but it was cut off when the ship finally lost power and began her final plunge.

Another interesting story is of Chief Baker Charles Joughin. Throughout the sinking, he calmly ran around the ship, gathering food and other provisions for the lifeboats, all the while tippling from a flask of Scotch. When he finished with that task, he then began tossing deck chairs and other unattached bits of wood overboard in the hopes of giving those in the water something to cling to. As the ship started her final dive, he was seen standing at the very stern, clinging to the flag pole (those familiar with the James Cameron movie will notice he included this). It is said the ship went under so smoothly that Joughin was able to step off of it into the water without ever getting his hair wet. He then swam to the overturned Collapsible B and tried to get on, but was refused. He clung to the side for a while, working his way around it, until eventually one of the cooks recognized him and held on to him so he wouldn't sink. Many believe he survived all that time in the water due to the amount of alcohol he had consumed, which may have helped warm him.

At 2:20am, Titanic sank beneath the surface of the Atlantic Ocean and would not be seen again for 73 years. Survivors in the lifeboats said that the sinking was followed by a terrible roar of voices as everyone in the water cried out to be saved. It was this sound that would haunt most of their dreams for years and years. In about twenty minutes, this sound would fade as they all died in the icy water. In most of the boats, someone would suggest they go back to pick up survivors, but the only one that actually did this was Officer Lowe in boat #14, after he tied up with the 3 other boats and moved his passengers off. A few other boats picked people up that happened to be near them, but in total, only 14 of the 1500 people in the water were taken into one of the lifeboats.

One of these saved is another interesting story, and another I suspect inspired James Cameron. It was told by Charlotte Collyer, who had volunteered to go back to the wreck site with Lowe in boat 14:

A little further on, we saw a floating door that must have been torn loose when the ship went down. Lying upon it, face downward, was a small Japanese [it was later determined he was actually one of 8 Chinese sailors who had signed on as firemen. Six of them survived.]. He had lashed himself with a rope to his frail raft, using the broken hinges to make the knots secure. As far as we could see, he was dead. The sea washed over him every time the door bobbed up and down, and he was frozen stiff. He did not answer when he was hailed, and the officer hesitated about trying to save him.

"What's the use?" said Mr Lowe. He's dead, likely, and if he isn't there's others better worth saving than a Jap!"

He had actually turned our boat around; but he changed his mind and went back. The Japanese was hauled on board, and one of the women rubbed his chest, while others chafed his hands and feet. In less time than it takes to tell, he opened his eyes. He spoke to us in his own tongue; then, seeing that we did not understand, he struggled to his feet, stretched his arms above his head, stamped his feet, and in five minutes or so had almost recovered his strength. One of the sailors near to him was so tired that he could hardly pull his oar. The Japanese bustled over, pushed him from his seat, took the oar and worked like a hero until we were finally picked up. I saw Mr Lowe watching him in open-mouthed surprise.

"By Jove!" muttered the officer. "I'm ashamed of what I said about the little blighter. I'd save the likes o' him six times over, if I got the chance."

All that was left now was to wait for rescue. Most of the officers were unaware of the Carpathia heading for them, so most of the lifeboats had no clue how long they would be adrift in the cold. With the exception of some bread brought up by Joughin and his bakers, many of the boats had no provisions.

At 3am, the Carpathia was nearing the Titanic's coordinates. Captain Rostrom ordered rockets to be shot off at 15 minute intervals so that they would know help was coming. Around 3:30, the first lifeboat spotted their rockets, and five minutes later, Carpathia had reached its destination. To Rostrom's confusion, the Titanic was nowhere to be seen. All that could be seen were small green lights every now and then down at the water line, which signaled the presence of small boats. He ordered the engines on standby, then at 4:00, ordered them stopped.

Ten minutes later, lifeboat #2 reached her side and officers began to bring the women up on board. Officer Boxhall, whose green rockets were probably the lights Rostrom saw, reported to the bridge and told Rostrom that Titanic had sunk at 2:20am.

Because it was so dark, the Carpathia stood still and let the lifeboats row to them. There was ice all around, and they were afraid that they might run into one of the small boats if they tried to move. (Pictured: Lifeboat #14 towing Collapsible D)

Because it was so dark, the Carpathia stood still and let the lifeboats row to them. There was ice all around, and they were afraid that they might run into one of the small boats if they tried to move. (Pictured: Lifeboat #14 towing Collapsible D)

The story of Officer Lowe in boat #14 continues here. Around dawn, as he was sailing towards the rescue ship, he noticed Collapsible D having trouble. It was riding low, with no crew on board to row it, so he tied it to his boat and towed it. Shortly after that, he found Collapsible A, filled with water and on the brink of sinking. About half of its passengers had frozen to death overnight, so he transferred the survivors onto his boat, pulled the plug in boat A and let it sink. Not far away, the upside-down Collapsible B was having difficulties. It couldn't be rowed anywhere, for obvious reasons, and the men standing on her bottom were getting tired from shifting their weight all night in an attempt to keep from sinking. Lightoller was one of these men, and had taken leadership of the group. He began to blow his whistle for help, and was heard by the three boats Lowe had tied together earlier, #4, #10 and #12. Men in #4 and #12 heard the whistle, untied themselves from #10 and rowed over. The first person to board #12 was baker Joughin, who was still in the water. Everyone else was transferred off of B into the two boats, then they all headed for the Carpathia.

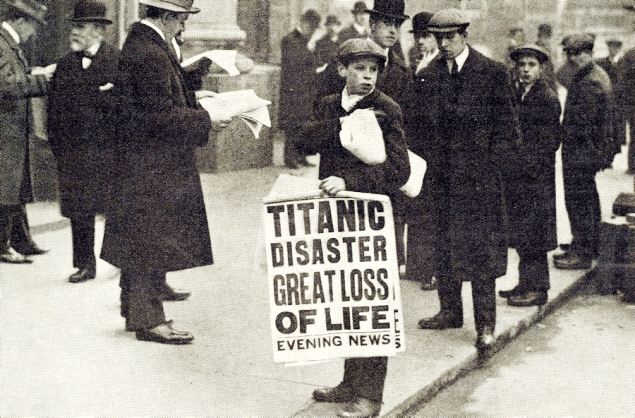

At 8:30am, the last lifeboat, #12, reached the Carpathia. Fifteen minutes later, Charles Lightoller climbed on board, the last person to be saved. Around this time, the Californian arrived on the scene, having finally gotten notice of Titanic's sinking a few hours earlier. Rostrom made another circle or two to search for survivors in the water, but saw nothing but some small debris, a few deck chairs and one body. He then left the Californian to continue searching and turned toward New York to deliver the survivors. They counted 705 brought on board, which meant over 1500 people had perished. Now all that was left was getting those survivors home, and starting the tedious process of notifying everyone of what had happened. The Carpathia's wireless operator was assisted by Titanic's surviving wireless man, Harold Bride, as they worked tirelessly to transmit the names of the survivors.

The Carpathia stopped once more along the way, around 4:00pm, to hold a memorial service for those lost, and to commit the four bodies they had on board (one taken from a lifeboat, the other 3 men who died after being rescued) to the sea.

Missed any stops on the Blog Tour? Here they are!

Twenty minutes after striking an iceberg, Captain Smith had been made aware of the ship's fate, and it wasn't a good one: Thomas Andrews estimated she had only an hour and a half or so left to live. Smith headed for the wireless room and told Phillips to start sending out their position with CQD (the international distress signal, which had recently been replaced by SOS, but most operators hadn't adopted the new code yet). Around 12:05, the first distress call was sent. At this point, the severity of the situation wasn't as clear, and Phillips and Bride made jokes as they sent their messages. (Photo is one of the icebergs seen the next morning that is a possible candidate for the one Titanic struck.)

Twenty minutes after striking an iceberg, Captain Smith had been made aware of the ship's fate, and it wasn't a good one: Thomas Andrews estimated she had only an hour and a half or so left to live. Smith headed for the wireless room and told Phillips to start sending out their position with CQD (the international distress signal, which had recently been replaced by SOS, but most operators hadn't adopted the new code yet). Around 12:05, the first distress call was sent. At this point, the severity of the situation wasn't as clear, and Phillips and Bride made jokes as they sent their messages. (Photo is one of the icebergs seen the next morning that is a possible candidate for the one Titanic struck.) Around 12:45, quartermaster Rowe began firing distress rockets. He would fire them at five-minute intervals for about 40 minutes. Meanwhile, the lifeboats were finally ready to be lowered. On the starboard side, First Officer Murdoch, Third Officer Pitman and Fifth Officer Lowe were in charge. Over on the port side, Lightoller was overseeing the boats with the help of Chief Officer Wilde and Captain Smith. Lightoller started by lowering lifeboat #4 down to A deck, where a group of wealthy first class passengers (including the Astors) were waiting. His intention was to load the boat from there, keeping them slightly warmer (the A deck promenade was enclosed) as they waited. But the screens could not be opened without a special tool, so he eventually had to give up and return to the boat deck, leaving #4 hanging there while he loaded the other boats.

Around 12:45, quartermaster Rowe began firing distress rockets. He would fire them at five-minute intervals for about 40 minutes. Meanwhile, the lifeboats were finally ready to be lowered. On the starboard side, First Officer Murdoch, Third Officer Pitman and Fifth Officer Lowe were in charge. Over on the port side, Lightoller was overseeing the boats with the help of Chief Officer Wilde and Captain Smith. Lightoller started by lowering lifeboat #4 down to A deck, where a group of wealthy first class passengers (including the Astors) were waiting. His intention was to load the boat from there, keeping them slightly warmer (the A deck promenade was enclosed) as they waited. But the screens could not be opened without a special tool, so he eventually had to give up and return to the boat deck, leaving #4 hanging there while he loaded the other boats. Because it was so dark, the Carpathia stood still and let the lifeboats row to them. There was ice all around, and they were afraid that they might run into one of the small boats if they tried to move. (Pictured: Lifeboat #14 towing Collapsible D)

Because it was so dark, the Carpathia stood still and let the lifeboats row to them. There was ice all around, and they were afraid that they might run into one of the small boats if they tried to move. (Pictured: Lifeboat #14 towing Collapsible D)

Sunday morning was clear but cool. After breakfast, church services were held in each class, with the first class service presided over in their dining saloon (photo, left) by Captain Smith. Some books claim that this was a all-class service, allowing third class up into the grand first class areas for a short time, but I'm hesitant to believe it. Steerage would never have been allowed into the first class areas. A similar service was held in the second class dining room by the assistant purser, Reginald Barker, and a Catholic mass was held in the second class lounge by Father Thomas Byles. (He also held a mass in third class.)

Sunday morning was clear but cool. After breakfast, church services were held in each class, with the first class service presided over in their dining saloon (photo, left) by Captain Smith. Some books claim that this was a all-class service, allowing third class up into the grand first class areas for a short time, but I'm hesitant to believe it. Steerage would never have been allowed into the first class areas. A similar service was held in the second class dining room by the assistant purser, Reginald Barker, and a Catholic mass was held in the second class lounge by Father Thomas Byles. (He also held a mass in third class.) After dinner, Rev. Carter organized a hymn sing in the second class dining room that was attended by close to 100 people. One hymn sung, by special request, was "For Those in Peril on the Sea." (The James Cameron film showed this being sung in first class during Captain Smith's church service. It may have been sung there as well.) Up in first class, a private party was being held in the a la carte restaurant in Captain Smith's honor, hosted by the Widener family. Rumors abounded after the disaster that the Titanic's maiden voyage was to be Smith's last (or nearly last), and that the party was in honor of his long career and impending retirement. Around 9:00, Smith left the restaurant to check in at the bridge. They knew they were entering an ice field, and he told Lightoller to keep a sharp eye out. Then, after instructing him to get him at any sign of trouble, he retired for the night. (Photo: First class a la carte restaurant, Olympic)

After dinner, Rev. Carter organized a hymn sing in the second class dining room that was attended by close to 100 people. One hymn sung, by special request, was "For Those in Peril on the Sea." (The James Cameron film showed this being sung in first class during Captain Smith's church service. It may have been sung there as well.) Up in first class, a private party was being held in the a la carte restaurant in Captain Smith's honor, hosted by the Widener family. Rumors abounded after the disaster that the Titanic's maiden voyage was to be Smith's last (or nearly last), and that the party was in honor of his long career and impending retirement. Around 9:00, Smith left the restaurant to check in at the bridge. They knew they were entering an ice field, and he told Lightoller to keep a sharp eye out. Then, after instructing him to get him at any sign of trouble, he retired for the night. (Photo: First class a la carte restaurant, Olympic) Titanic was a huge ship with a relatively small rudder for her size, which meant she didn't turn quickly. She did eventually turn, but not soon enough. While they avoided a head-on collision, they didn't get out of the way in time, and the iceberg scraped along the starboard side of the ship. It was barely felt in most areas—little more than a faint vibration—but most passengers who were awake at the time reported feeling or hearing something. The men still playing cards in the second class smoking room claimed to have seen the iceberg itself pass the room's windows, but aside from some of the officers who had been watching the collision, the only other physical evidence in the passenger areas were the chunks of ice that had broken off of the berg and fallen onto the decks and into a few open portholes. Below decks, however, the damage was much more apparent. Water began to fill the forward holds and boiler room #6 immediately, and with great force.

Titanic was a huge ship with a relatively small rudder for her size, which meant she didn't turn quickly. She did eventually turn, but not soon enough. While they avoided a head-on collision, they didn't get out of the way in time, and the iceberg scraped along the starboard side of the ship. It was barely felt in most areas—little more than a faint vibration—but most passengers who were awake at the time reported feeling or hearing something. The men still playing cards in the second class smoking room claimed to have seen the iceberg itself pass the room's windows, but aside from some of the officers who had been watching the collision, the only other physical evidence in the passenger areas were the chunks of ice that had broken off of the berg and fallen onto the decks and into a few open portholes. Below decks, however, the damage was much more apparent. Water began to fill the forward holds and boiler room #6 immediately, and with great force. For everyone else on board, April 13 was a normal, perhaps even boring, Saturday at sea. Nowadays, cruises are packed from minute to minute with things to do, but in 1912, the only organized activities were three meals a day and a church service on Sunday morning. The rest of the time, passengers entertained themselves. Saturday was a sunny day, but still cool, so most people probably stayed indoors, reading or writing in the libraries. Here is a quote from second class passenger Lawrence Beesley, from his book, The Loss of the S.S. Titanic. (Photo is Titanic's second class library, though more likely a photo of Olympic.)

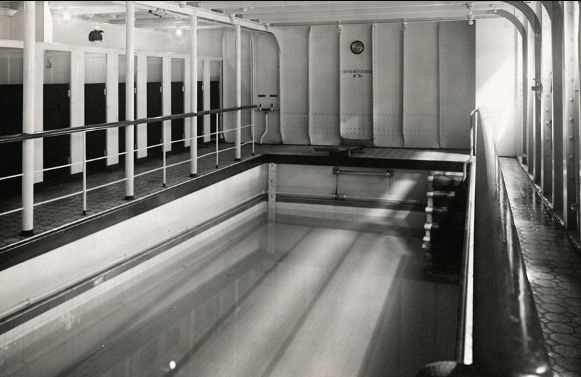

For everyone else on board, April 13 was a normal, perhaps even boring, Saturday at sea. Nowadays, cruises are packed from minute to minute with things to do, but in 1912, the only organized activities were three meals a day and a church service on Sunday morning. The rest of the time, passengers entertained themselves. Saturday was a sunny day, but still cool, so most people probably stayed indoors, reading or writing in the libraries. Here is a quote from second class passenger Lawrence Beesley, from his book, The Loss of the S.S. Titanic. (Photo is Titanic's second class library, though more likely a photo of Olympic.) The next two days on Titanic were relatively uneventful. The ship was at open sea, with nothing but water for miles in all directions. Passengers would spend their days wandering the decks when the weather was warm enough, chatting or reading in the lounges or libraries, playing cards, and for the first class, checking out the amenities available. There was the Turkish bath, swimming pool, squash court and gymnasium, all with special hours for men and women separately (no co-ed swimming, it would seem). The gym even had a special children-only opening each afternoon. Not all of these rooms were free, but the first class could afford an extra dollar or two for the added luxuries. The swimming pool was salt water, filled once Titanic was out to sea, and was heated. It was one of the first ships to have a swimming pool (or swimming bath) on board.

The next two days on Titanic were relatively uneventful. The ship was at open sea, with nothing but water for miles in all directions. Passengers would spend their days wandering the decks when the weather was warm enough, chatting or reading in the lounges or libraries, playing cards, and for the first class, checking out the amenities available. There was the Turkish bath, swimming pool, squash court and gymnasium, all with special hours for men and women separately (no co-ed swimming, it would seem). The gym even had a special children-only opening each afternoon. Not all of these rooms were free, but the first class could afford an extra dollar or two for the added luxuries. The swimming pool was salt water, filled once Titanic was out to sea, and was heated. It was one of the first ships to have a swimming pool (or swimming bath) on board. One thing of note did occur on the 12th, however, that would affect the rest of the ship's voyage. Around 11pm, the wireless broke down, and while the wireless operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, were able to fix it early the following morning, the brief outage caused a pretty serious backlog of messages to be sent. Because they allowed passengers to send messages through the wireless (for a fee, of course), the operators were kept busy. Wireless was still a novelty, and those who could afford it couldn't seem to resist sending a message back home from the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. The next few days, Phillips and Bride would be working at a fever pitch to catch up on the messages waiting to be sent, and would not have time to get all the ice warnings to the bridge, often giving precedence to the passenger communications over the ice notices. They were employed by the Marconi company, not the White Star Line, so those passenger messages were a big part of their business. (Not to say they ignored ice warnings. Anything coded to be given to the captain was immediately sent up, but not all incoming messages about ice were coded as such, and therefore were not always considered urgent by the busy wireless operators.)

One thing of note did occur on the 12th, however, that would affect the rest of the ship's voyage. Around 11pm, the wireless broke down, and while the wireless operators, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, were able to fix it early the following morning, the brief outage caused a pretty serious backlog of messages to be sent. Because they allowed passengers to send messages through the wireless (for a fee, of course), the operators were kept busy. Wireless was still a novelty, and those who could afford it couldn't seem to resist sending a message back home from the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. The next few days, Phillips and Bride would be working at a fever pitch to catch up on the messages waiting to be sent, and would not have time to get all the ice warnings to the bridge, often giving precedence to the passenger communications over the ice notices. They were employed by the Marconi company, not the White Star Line, so those passenger messages were a big part of their business. (Not to say they ignored ice warnings. Anything coded to be given to the captain was immediately sent up, but not all incoming messages about ice were coded as such, and therefore were not always considered urgent by the busy wireless operators.) The morning of April 11 was clear but cool, keeping most passengers indoors as the Titanic neared her final stop in Queenstown, Ireland (known today as Cobh). She docked around 11:30am, dropping anchor just outside of Roche's Point, too big to berth at the dock itself. Passengers and mail had to be ferried back and forth on smaller tenders.

The morning of April 11 was clear but cool, keeping most passengers indoors as the Titanic neared her final stop in Queenstown, Ireland (known today as Cobh). She docked around 11:30am, dropping anchor just outside of Roche's Point, too big to berth at the dock itself. Passengers and mail had to be ferried back and forth on smaller tenders. While Titanic is in port, newsmen and others are allowed on board to quickly tour her decks, take pictures and even sell wares to the first class passengers. But not for long, because about two hours after dropping anchor, she is ready to set off again, this time for New York. The photo to the right was taken by Father Browne as he left the ship, the last picture ever taken of Captain Smith, who can be seen peering down from the bridge (top of the image), with one of the lifeboats dangling ominously below.

While Titanic is in port, newsmen and others are allowed on board to quickly tour her decks, take pictures and even sell wares to the first class passengers. But not for long, because about two hours after dropping anchor, she is ready to set off again, this time for New York. The photo to the right was taken by Father Browne as he left the ship, the last picture ever taken of Captain Smith, who can be seen peering down from the bridge (top of the image), with one of the lifeboats dangling ominously below.

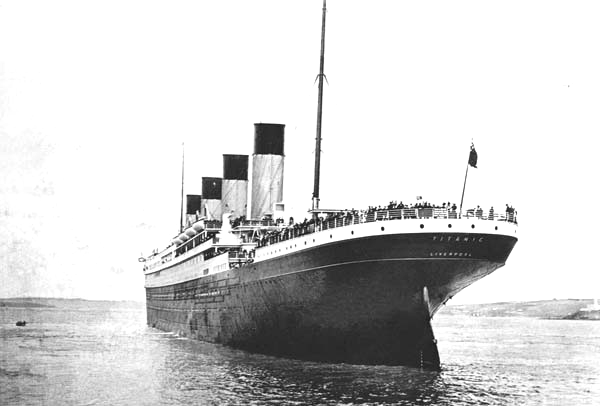

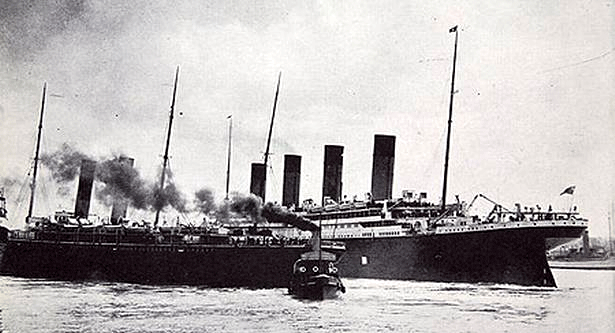

April 10 was a busy day for Titanic. It was sailing day, the first day of her maiden voyage. She would set off from her first port in Southampton, England, at noon, heading across the English Channel for Cherbourg, France.

April 10 was a busy day for Titanic. It was sailing day, the first day of her maiden voyage. She would set off from her first port in Southampton, England, at noon, heading across the English Channel for Cherbourg, France. At noon, the ship began to edge away from the dock. As she turned into the channel to head out, her size and increasing speed churned up the water enough that a suction was created, pulling two nearby ships, the Oceanic and New York away from their moorings. Ropes snapped, and the New York was set free. Captain Smith was made aware of the imminent danger and went into action, calling for the engines to be reversed, halting her movement. The New York was corralled by tugs and stopped before Titanic began to move forward again. While this was going on, more lines were added to Oceanic to prevent her from breaking free, and after a tense hour, Titanic was once again on her way. Her voyage had begun, but the incident with the other ships had delayed her an hour, and she would now arrive at her next destination late. A bad omen?

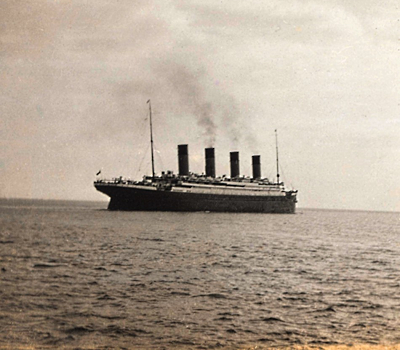

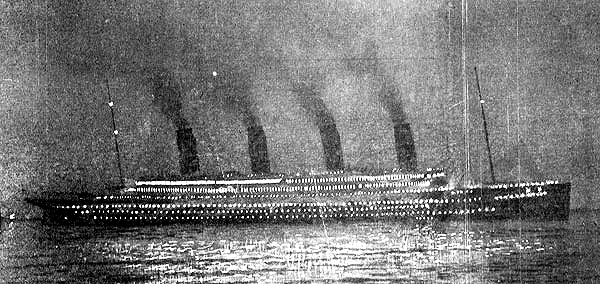

At noon, the ship began to edge away from the dock. As she turned into the channel to head out, her size and increasing speed churned up the water enough that a suction was created, pulling two nearby ships, the Oceanic and New York away from their moorings. Ropes snapped, and the New York was set free. Captain Smith was made aware of the imminent danger and went into action, calling for the engines to be reversed, halting her movement. The New York was corralled by tugs and stopped before Titanic began to move forward again. While this was going on, more lines were added to Oceanic to prevent her from breaking free, and after a tense hour, Titanic was once again on her way. Her voyage had begun, but the incident with the other ships had delayed her an hour, and she would now arrive at her next destination late. A bad omen? The sun was beginning to set as Titanic finally arrived at the French port. She dropped anchor around 6:30pm and tenders began to ferry the cross-channel passengers and mail off. Other tenders carried the Cherbourg passengers to the ship, along with more mail. The entire process took about 90 minutes, and by 8:00pm, the sun had set and she was ready to set off for Ireland, lights blazing from every porthole. She must have been quite the sight to behold. The photo here was taken shortly after she dropped anchor, before it was fully dark.

The sun was beginning to set as Titanic finally arrived at the French port. She dropped anchor around 6:30pm and tenders began to ferry the cross-channel passengers and mail off. Other tenders carried the Cherbourg passengers to the ship, along with more mail. The entire process took about 90 minutes, and by 8:00pm, the sun had set and she was ready to set off for Ireland, lights blazing from every porthole. She must have been quite the sight to behold. The photo here was taken shortly after she dropped anchor, before it was fully dark.